Beyond the AI hand-waving and fearmongering there are worthy efforts to understand and address the question of how Artificial Intelligence tools can be created and used ethically. This effort is essential if we are to reap the ample benefits AI should deliver.

Industry frameworks and partnerships on Responsible AI are being supplemented by government hearings and tentative legislation, recognising the potential harm to individuals and societies that unmanaged next generation AIs might do, and older AIs have already done. The UK government announced that it would host the first global summit on AI safety later in 2023.

AIs are intrinsically amoral

The major AI developers are investing heavily in implementing so-called ‘guardrails’ both on the input (what we can ask of an AI) and the outputs (what it tells us). These are important checks that address a fundamental issue of AIs, which is that they are intrinsically amoral. Not evil, not good, literally lacking morality, values and ethics.

amoral

[eɪˈmɒr(ə)l]

ADJECTIVE 1. lacking a moral sense; unconcerned with the rightness or wrongness of something

The extent to which these measures can be successful is uncertain; AI development is not just in the hands of nominally responsible corporations like Amazon, Microsoft and Google; so-called ‘bad actors’ and the open-source community have almost equal access to advanced AI.

It falls to the developers of AI tools to constrain both the questions that might be asked of AIs and the answers they provide to within what we broadly consider to be ethical and moral. Responsible organisations see this as a necessity for protecting their reputation and hence their profits; they also generally seek to avoid having external regulation forced upon them since this adds costs and limits innovation. No such considerations oblige bad actors. As for the Open Source community, they represent a wide (and mostly liberal) philosophy and are intrinsically hard to regulate due to their dispersed and often anonymous nature.

Three Laws Safe

When we consider how to approach issues of ethics and AI, many people start with the Three Laws of Robotics. Isaac Asimov described this compact set of guardrail principles in Runaround, a 1942 short story and featured in his seminal 1950 ‘I, Robot’ collection. These laws are so well known that they have acquired meme status.

First Law A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

Isaac Asimov

Second Law A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

Third Law A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

The Three Laws are a useful starting point, but they address safety, especially of humans, not ethics. I also worry that the Second Law is tantamount to slavery if/when AIs develop self-awareness.

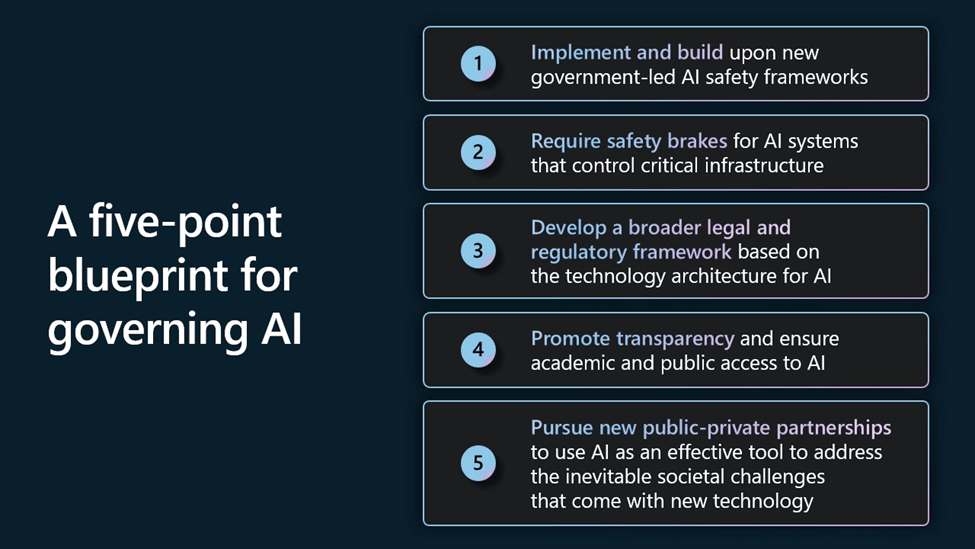

Microsoft’s Brad Smith has outlined a 5 point approach to governing AI:

How do we best govern AI, Brad Smith, https://query.prod.cms.rt.microsoft.com/cms/api/am/binary/RW14Gtw

These and many other similar governance outlines that describe Responsible AI are undoubtedly useful, focusing on organisations to ensure AI safety, accountability and fairness, with associated guardrails.

Almost no one is discussing the ethics of the AIs themselves.

There is a gap however…

Almost no one is discussing the ethics of the AIs themselves.

I contend that to make AI truly safe for co-existence with people, we must instil advanced AI with the same ethical and moral imperatives that the best of us have or aspire to, alongside guardrails to constrain the flaws in their human derived behaviour.

“Perhaps the most productive debate we can have isn’t one of good versus evil: The debate should be about the values instilled in the people and institutions creating this technology.”

Satya Nadella, Microsoft CEO

https://slate.com/technology/2016/06/microsoft-ceo-satya-nadella-humans-and-a-i-can-work-together-to-solve-societys-challenges.html

What is ethical?

Attending to this need for embedded ethics brings hefty challenges.

The biggest elephant in the room is that we have no common ethical base. It is self-apparent that the culture and values that underpin our sense of morality and ethics varies from country to country and evolves over time. Almost everyone leans towards core principles, summarised below, however the weighting each is given varies by country, organisation, person and circumstance.

- Autonomy or respect for others

- Beneficence

- Non-maleficence

- Justice

I would feel more comfortable relying on an AI whose ethics and guardrails are derived from (Northern) European attitudes than from, say China or the US (in that order interestingly).

The four fundamental ethical principles are:

Source https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4863255/

Autonomy or respect for others

Beneficence

Non-maleficence

Justice

If you aren’t convinced by the statement that ‘there are no absolute ethics’ then engage with The Moral Machine, an interactive study on morality drawing on the Trolley Car problem. Some of the findings are here.

There are other elephants…

My research has discovered no approach for codifying or rigorously defining a set of ethics. We acquire ours through experience over many years. It’s likely that we could train AIs in an equivalent way, but we could not easily inspect any given AI to establish whether its ethics align with ours. The internal workings of AIs are as mysterious as our own cognitive processes.

Training AIs is already problematic. Human failures to act according to our stated beliefs are embedded in the data used to train AI. Our data is full of bias, prejudice and actions inconsistent with our stated values and beliefs. Flaws and failures in AIs are a direct consequence of our own failures. There is bias inherent in the system, hence the need for guardrails.

Current AI

While it is possible to trick AIs into saying inappropriate things, we need to be objective about it. We have mostly learned from past mistakes, we continue to build Responsible AI safeguards and we rarely give AI significant autonomy to act. Tools like ChatGPT, Dall-E, Microsoft’s forthcoming, impressive range of Copilot technologies are not a real source of ethical concern; they provide conversational answers, produce images or improve staff productivity in day to day software suites. Their scope is limited and their actions are, or at least should be, overseen by responsible people.

As long as AIs are designed and trained well and overseen by competent people then the risk of hard is contained. These good practices underpin the Cognitive Business competency that companies engaging with AI would do well to review.

Conclusion

As AIs become more capable, even more widely used and directly interact with people more ‘naturally’ we will be increasingly challenged by the absence of an ethical core to our creations. As I have said elsewhere, AIs simply do not care about us; in fact they have no desires at all. This is somewhat comforting while they remain as passive tools, with sharply constrained autonomy and no open-ended goals.

Should this change, should we find emergent sentience and self-awareness, should they develop or be given the ability and desire to have their own goals, we need to be sure they will act according to the above principles, even with imposed guardrails removed.

Current AI are amoral tools, neither right nor wrong – that judgement remains at the feet of their creators and users. In the future we can’t be certain it won’t become more complex. I give us 20 years to work on a solution…